Exploring Vietnam’s COVID-19 Success

Lessons From ‘Unlikely’ Places

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced a global reckoning: From shortages of PPE to intermittent lockdowns, nations are wrestling with the fact that they were ill-equipped to control a virus that scientists have been predicting for decades.

In the wake of this realization, international organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and governments are improving the world’s pandemic response. Hundreds of nations are joining COVAX, a global vaccine-sharing mechanism; the World Health Organization is weighing reforms after criticism; and nations are updating their economic policies to improve resilience.

However, just as important as understanding what we can learn is acknowledging from whom we can learn it.

Vietnam: Success Against the Odds?

Among the world’s COVID-19 success stories, Vietnam has gone largely unnoticed. While The New York Times rightfully marveled at New Zealand’s apparent pandemic victory in June, Vietnam, whose first confirmed case appeared in January, had yet to report a single COVID-19-related death.

When a Time Magazine article published a list of the world’s best pandemic responses—praising Canada and Germany, among others—Vietnam, on nearly 70 days without community spread, was conspicuously absent.

Though new outbreaks have occurred, Vietnam’s success has continued: At the time of writing, the country of 97 million people has reported only 35 total deaths and 1,283 cases.

In the context of COVID-19, Vietnam is disadvantaged: It shares a border with China, where the virus originated; it is a low-middle income country; and its dense population is conducive to rapid community spread. So why do Vietnam’s numbers diverge so drastically from most nations?

Vietnam Is No Stranger to Infectious Diseases

In 2003, Vietnam experienced a SARS outbreak that infected dozens. The following year, Avian Flu clusters appeared across the country—a scourge that would take over ten years to quell. Turning tragedy into opportunity, Vietnam used these epidemics to fine-tune its infectious disease response.

The Southeast Asian nation invested heavily in its public health infrastructure, establishing a network of emergency operations centers for rapid response to outbreaks and creating a centralized database of infectious disease patients. Vietnamese policymakers, learning from past failures, developed plans to quickly restrict travel and movement should a new virus emerge. The country was preparing for the worst.

Prevention and Mitigation

That preparation was prescient. In December 2019, the first case of COVID-19 appeared in Wuhan, China—and the virus quickly spread to over 20 countries by late January 2020. At that time, when most nations reacted with ambivalence, Vietnam was decisive.

On January 24, the day after Vietnam’s first case, aviation authorities canceled all flights to and from Wuhan. Within a week, the authorities expanded the cancellations to include all of China. Soon, the Ministry of Education and Training successfully pushed a nationwide school closure—subsequently extending the policy for the remainder of the academic year.

Other public health measures kept outbreaks isolated. By February 7, research institutions had already developed inexpensive COVID-19 tests, and production was quickly scaled up to distribute these tests at the national level. Health officials also implemented comprehensive contact tracing, which led to the proactive quarantine of individuals based on exposure—not on symptoms.

Worth noting was the Vietnamese people’s quick behavioral shift—a result of both public conscientiousness and strategic government messaging.

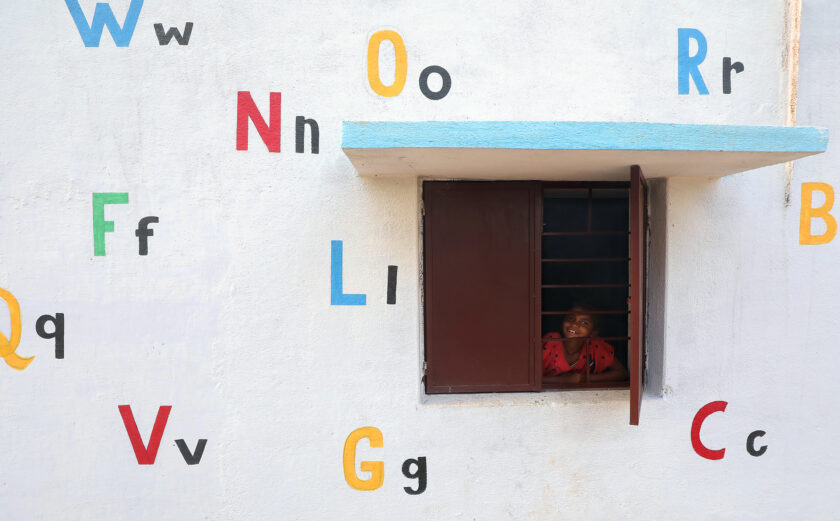

To encourage hygienic practices, the government of Vietnam pursued a massive educational campaign. To reach youth, for example, the Ministry of Health produced a catchy Coronavirus song, sparking a viral Tik Tok dance challenge. The Song, which was featured on John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight, teaches viewers to wash their hands and wear face masks to “push back” the “cruel” disease.

However, these messages were likely preaching to the choir: In Vietnam, wearing masks to protect against pollution was already standard; unsurprisingly, wearing masks to protect against COVID-19 became decidedly uncontroversial. The memory of SARS and Avian Flu, moreover, likely contributed to the public’s resolve.

Challenges in Replication

To be sure, Vietnam’s pandemic response is not beyond reproach, and it may not be replicable in other countries—especially democracies. Critics rightfully point out that Vietnam’s centralized, single-party government allows it to make sweeping policy decisions without public discourse or government gridlock. Further, without the widespread emphasis on “personal freedoms” that exists elsewhere, restrictive control measures pass without dissent.

Still, to dismiss Vietnam’s success is unwise. The international community often views the transfer of innovative policies and best practices as a process that naturally flows from developed countries to developing ones—or from the “Global North” to the “Global South.” Whether dealing with climate change mitigation or improving livelihoods, developing countries are rarely viewed as the facilitators of their own success and are often removed from the conversation. This paradigm is more than just patronizing: It prohibits learning and growth.

To improve its pandemic response, the world must acknowledge that lessons may come from “unlikely” places.