Effectively Measuring Early Childhood Learning and Development

Communities cannot rise out of poverty if their children do not thrive.

That’s why early learning education and development programs that set a strong foundation for a child’s capacity to learn throughout life — across cognitive, social-emotional and language domains — are critical to later success. The importance of early childhood education and development programs is highlighted in the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4.2, “by 2030, all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care, and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education.”

Many approaches are being undertaken around the globe. However, the lack of robust evidence from impact evaluations has been a challenge to achieving access, equity and quality in early childhood education (ECE). It was difficult comparing disparate data from varying countries’ education evaluations. Our sector was in need of an effective global assessment tool that accurately measured, aggregated and shared the data across multiple contexts.

In response, Save the Children developed IDELA, the International Development and Early Learning Assessment. IDELA is an open-source tool that measures four key areas of early development: social-emotional skills, emergent numeracy, emergent literacy, and motor skills in children ages 3.5 to 6 years. With IDELA, every child is a “data point” and feeds into a collaborative, global knowledge that is aggregated to evaluate effective strategies in early education. IDELA is now used in 70+ countries. My organization, Food for the Hungry (F.H.), has launched it in 13 countries where we work, one of its biggest rollouts.

IDELA allows F.H. to share a common language across different countries. When we refer to “emergent literacy”, for example, our staff around the world automatically think of skills such as print awareness, expressive vocabulary, and letter recognition. Implementing IDELA has made us better informed about our targeted early learning interventions. This means we can ameliorate, implement, and advocate for the youngest among us more effectively.

Here are three brief case studies highlighting where IDELA has helped F.H. transform and improve ECE:

Emergent Literacy

Overall low IDELA assessment scores revealed to our local staff in Burundi that children were not acquiring the skills needed for a successful transition into first grade. Emergent literacy was the lowest-ranked domain, which spurred a two-fold approach to increase language development skills.

F.H. established common play areas in the community. Areas where children are able to sing songs and use expressive vocabulary to communicate more with peers. At home, F.H. is training parents and caregivers through Care Groups to have more conversational interactions with their children, including using higher-level vocabulary in daily life. Households are taught to involve young children in daily activities, such as outings to local shops and markets and learning to name items. We also encourage elevating expressive vocabulary with pictorial books that parents or older children can read together. When our Burundi staff was not able to find stories and resources in local languages, they participated in a book translation challenge. This resulted in 158 different children’s books translated into the local language.

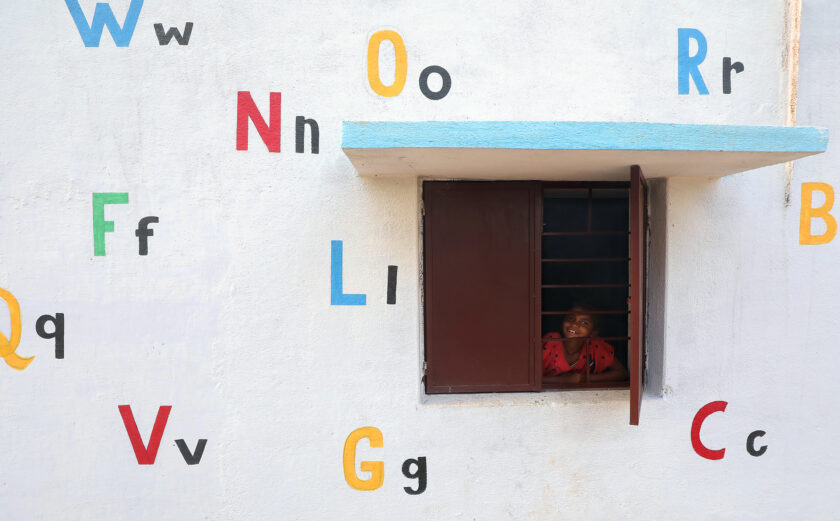

A world away, children in the Dominican Republic (D.R.) also scored low in emergent literacy, especially expressive vocabulary. As a result, our local D.R. staff recommended building community libraries and establishing “parent schools” in 52 neighborhoods where parents are taught early stimulation practices. By engaging children through books and storytelling, children learn to identify symbols and letters that will be the building blocks of their literacy development. We have equipped parents with appropriate tools, even parents who are illiterate.

Social-Emotional Skills

In the D.R., the IDELA assessment revealed a surprising trend. Social-emotional skills among children was the second-highest domain after motor skills, the opposite of trends we’ve seen elsewhere. The social-emotional skills domain usually scores the lowest (our hunch is that the social, Caribbean culture here inherently strengthens these skills within and between families). In contrast to the D.R., we learned small gains were being made in social-emotional development in Guatemala.

A child’s social-emotional development is as important as their cognitive and physical development. However, we are not born with skills such as empathy or awareness of our own feelings; it takes practice. IDELA data revealed to our Guatemalan staff that children do not play together often. Our staff began encouraging play and providing games and materials to help build early social capital. Early stimulation training modules were also implemented into their Care Groups. Additionally, they are also raising awareness about social-emotional learning with others who interact with young children, including healthcare facility workers and pre-school teachers.

Emergent Numeracy

When children in Bangladesh scored low across the four IDELA areas, F.H.’s Bangladesh staff took a closer look at the data. Our staff identified emergent numeracy as a particularly struggling domain, with 40% of children completing less than half the activities correctly on the IDELA assessment.

In response, our staff determined local preschool teachers needed improved training and classroom materials such as number charts, posters of different geometric shapes, and basic arithmetic resources to improve number recognition. In addition, staff encouraged caregivers to involve children in daily activities like counting chickens and other livestock. They also highlighted the importance of caregivers setting time aside to interact with their children as they went about their daily chores.

Consistent assessment makes a qualitative difference

IDELA has become critical to informing the work of our early childhood development practitioners, filling in gaps that lead to more effective outcomes. We hope this innovative measurement tool will lead to even more holistic approaches. Some that will encompass spiritual or invisible dimensions of overcoming poverty, such as the emergence of hope and care for others. When we better understand and meet the early needs of every child, encouraging them to flourish in every sphere, that “data point” and “outcome” will be a child with a more promising future.

About the author:

Jana Torrico is the Senior Specialist of Global Education Programs for Food for the Hungry, an international relief and development organization graduating communities from extreme poverty in over 20 countries worldwide.

This piece was originally published on the Basic Education Coalition blog on 01/24/20.