Human Rights Day 2021: Fighting for Equality in the COVID Age

25 years ago, the United Nations General Assembly declared that development is a human right. Recognizing development as a process that contributes to peace, security, and the well-being of communities, the 1986 Declaration is a testament to the interconnection of development with the “fundamental freedoms” of people all over the world.

This year’s U.N. Human Rights Day offers space to be reminded of what can no longer be ignored: the time for advocacy and action is now.

This year’s theme is Equality—reducing inequalities, advancing human rights. Amid the rise of COVID-19, this theme is more relevant than ever before. In order to properly address the realities of equality today, it is important to recognize how COVID-19 has impacted varying sectors of development.

Our Fall 2021 Global Development Policy and Learning intern cohort prepared this blog to highlight key development sectors most impacted by the pandemic and to lay a path forward.

Locally-led Development

Over the years, there have been increased calls to re-examine the role of international development in low- and middle-income countries. Global development is no longer accepted as a “neutral” field that allows Western actors to play savior—activists, practitioners, and actors worldwide are rightfully calling out the field for its perpetuation of colonial power imbalances and its roots in structural racism. These discussions became especially pertinent following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, forcing the global development sector to face these issues of systemic and structural inequities head-on.

The COVID-19 pandemic has concurrently transformed the landscape of international development operations. At the outset of the pandemic, many organizations repatriated their “international” staff to their home countries, leaving “local” staff to pick up the pieces and continue implementing their organization’s work. This created a visible gap in the sector—those who are “qualified” to carry out development work and be “protected” in the face of a global health crisis—and those who are not.

Advancing locally-led development is a key part of shifting power in the international development space. The notion that “local” or “national” actors do not have the capability to take the lead in this work couldn’t be further from the truth. As Alex Martins of CDA Collaborative points out, this call for shifting power in development is not new. Yet the pandemic—and the sector’s response to it—is just another unveiling of the power imbalance that exists. Collectives making strides in this work include Population Works Africa and the #ShiftThePower movement.

Vaccine Inequality

Vaccine inequality between wealthy and poor countries endangers the fundamental human right to health for every individual on the planet. Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, about 35% of the people who have received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine are from high-income countries. Vaccination rates in some low-income countries, including Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo, are less than 1%. It is estimated that wealthy countries could have a surplus of more than 1 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses not yet designated for donation to poorer nations.

Recent developments of the Delta and Omicron variants are sobering reminders that the virus will continue to mutate and spread if the vaccination of people globally is not prioritized. Ultimately, those most marginalized will be disproportionately harmed; meaning those who reside in low-income countries which cannot afford to purchase vaccines, those affected by armed conflict; incarcerated individuals;, Indigenous peoples and people of African descent; the poor; and the unhoused.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to exacerbate existing inequalities throughout the world, it is clear that the right to vaccination has undoubtedly become a human right. Global vaccination is just the first step to ending the pandemic, but vaccine inequality must be addressed before we can even consider meeting that goal.

Hunger and Malnutrition

Having equal access to individually sufficient foods and being free from hunger are both human rights that are far from being equitably met. The COVID-19 pandemic has, thus far, increased global food insecurity in almost every country by reducing incomes and disrupting food supply chains.

As the pandemic rages on, the poorest and most vulnerable populations are most dramatacially impacted and experience the greatest devastation. In 2020, nearly one in three—2.37 billion—people did not have sufficient access to food, forcing over 34 million people into “emergency” levels of food insecurity. The intertwined relationship between conflict, climate shocks, and economic downturns are expected to exacerbate hunger through the remainder of 2021 and well into 2022, making the global goal of Zero Hunger by 2030 even farther from reach.

However, change is possible. Based on recommendations presented in InterAction’s 2021 Famine Risk & Prevention Spotlight Report, all members of the international system must improve their ability to prevent the worst effects of hunger crises before they happen. Taking early action will save lives, promote equality, and set a precedent of prevention rather than reaction—a tool the international human rights and development community must adopt.

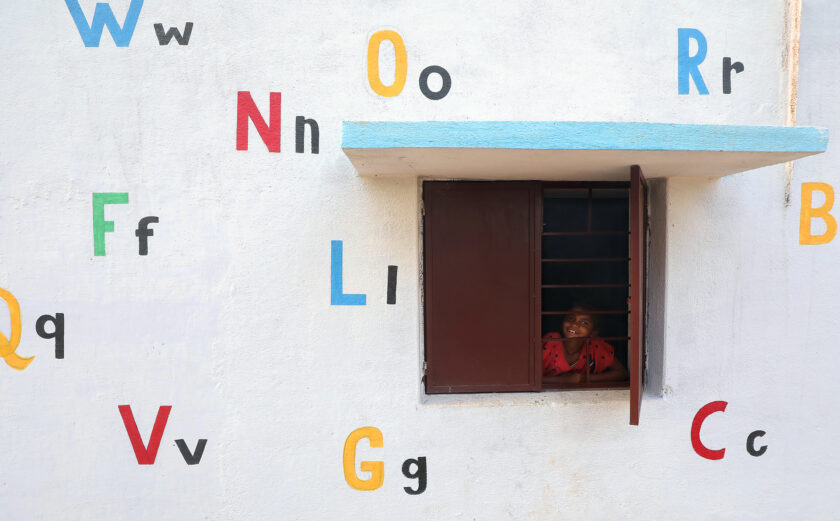

Quality Access to Education

Applying a human rights approach to education is also necessary to adequately address the secondary impacts of COVID-19 and ensure solutions do not exacerbate existing inequalities.

Today, UNICEF fears that 117 million students are currently out of education. As the pandemic persists, school closures and online learning has disrupted education for an estimated 90% of the world’s school-aged children. As students who are fortunate enough to return to school when it is safe do so, there are important ways that activists and policymakers should be considering the intersection of education and human rights.

The pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing inequalities. School closures have not affected all students equally, and students in the most at-risk communities have not been given the opportunities, tools, or access to continue their education. UNICESCO suggests that 50% of learners who lost access to in-person instruction had no access to a household computer. As many as 43% of online learners have no internet access, a figure that skyrockets to 82% in sub-Saharan Africa. States’ reliance on online instruction only intensified the unequal distribution of educational resources and support.

In order to address the structural factors that allowed these acute inequalities to persist, states should promote a more holistic approach to the right to education as a larger socialization process. Only then will we structurally and meaningfully transform our approach to education.

Looking Ahead

The time to transform global development work is now. InterAction is committed to modeling the change we wish to see as a leader and convenor in the sector. USAID Administrator Power’s commitments to make aid more accessible and responsive recognizes the important steps the development sector has taken to advance equity and locally-led change.

This progress cannot stop here. InterAction is dedicated to advocating for a whole-of-government approach to ensure power flows to those who face vaccine inequality, hunger, and limited access to quality education.