Storytelling as Activism: Part 4

Using Innovative Programming and Cultural Immersion to Enhance the Voice of Marginalized Populations

When designing development programs, the idea that “this is how we have always done it,” needs to be left at the door. However, if my 5+ years of experience in programming has taught me anything, it’s that this is easier said than done.

Three years ago, I pitched the idea that there is no need to produce social media 101 classes for civil society organizations (CSOs), activists, and political parties overseas. Instead of training participants on how to use Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, I argued we should teach them how to tell their stories more effectively.

When I voiced this to program teams, they looked at me like I was crazy. Why would we not teach participants social media 101? Those were the hard skills they needed!

Then, a young woman named Meryl, who worked in the Asia department, came to me and said, “I think you are right.”

That is when the out-of-the-box digital storytelling program strategy was born. Funders loved it.

After three years of training activists in closed and closing spaces on digital storytelling, Meryl came back with a question—could we tailor the digital storytelling curriculum for the Lao context and teach youth in-country how to tell the story of marginalized populations through photography and cultural immersion?

The resulting Digital Storytelling Curriculum proves that NGOs of all sizes must bring innovation and forward-thinking into program design to secure funding and guarantee results. The purpose of this work is no longer to teach participants the hard skills needed to get “through the door” of social media advocacy. The purpose is to empower them with the passion for storytelling necessary to take these digital platforms and use them for real results.

What made this training innovative?

We recruited new young participants by calling the training a “camp” and partnering with a university.

How many times have the same participants rolled through different trainings? Training the same people over and over again does not improve outcomes. But, in challenging spaces, how do you find new people to work with? The training was hosted at the local university and was marketed to the students as a Digital Storytelling Summer Camp. Campers, who were hand-selected, received hands-on training and learned new ways to tell their stories online.

We got out of the conference room and into the field.

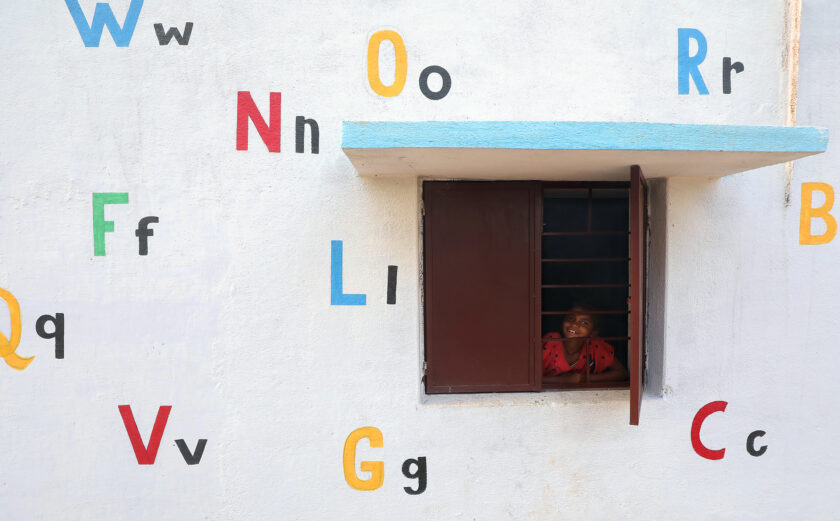

Unlike many workshops, the Digital Story Camp was not held entirely in a conference room. Campers went on excursions to small villages where many marginalized populations reside, visited women-owned businesses, toured a museum on the history of Laos, and met with students at a school for the deaf and mute. During that time, campers interviewed people and took photos—telling the stories that far too often go untold.

We got comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Sometimes feeling uncomfortable is the key to success. My first task when I train is to ask the participants what they expect to get out of the training. After they respond, I let them know what I expect from them. That is when they learn about the three answer rule. When I ask participants questions, I need at least three answers. If three people do not raise their hands, I call on people randomly. The three answer rule makes a room a bit uncomfortable at times. However, every time I enforce it, bigger, better, and more innovative ideas surface.

We used competition to our advantage.

Competitive people create change. Most people don’t comprehend the sheer amount of drive necessary to truly make a difference. When one assembles 10 young people who are excited to drive change, competition is inevitably going to emerge. This can either help or hinder the training; teaching participants to harness it productively is of the utmost importance.

At the beginning of the camp, we told the participants the big game-changer: the person who made the best digital story by the end of camp would get to go on an all-expense-paid trip to a youth summit in Europe.

Throughout the camp, I never had to ask participants to put down their phones or to pay attention. They took notes religiously. When I offered one-on-one consults, all but one participant signed-up. At every consult, the same question appeared: “How can I win this competition?”

We ditched the pre- and post-tests.

I never thought monitoring and evaluation could be cool until I met Meryl. Think about it: when did pre- and post-tests ever inspire? Have you ever been able to measure if your program made a real change through multiple choice questions? By facilitating user-driven, highly participatory learning methods, we challenged campers to think deeply about the outcomes of their digital story and allowed the facilitators to take a step back and watch the participants take the lead in their own learning.

Conclusion

Advocacy programming is constantly changing, and it’s vital that NGOs always push themselves to question the status quo and take risks. By flipping the “social media 101” training model on its head, Meryl and I discovered new ways to train young advocates while pushing them to take control of their own learning. We’ve learned that, by cultivating their passion instead of only focusing on hard skills, we can forge a new generation of young advocates who are excited to create change and prepared for whatever comes next.

And I can’t wait to see what comes next.