Strengthen the Global Community Through Educational Investments

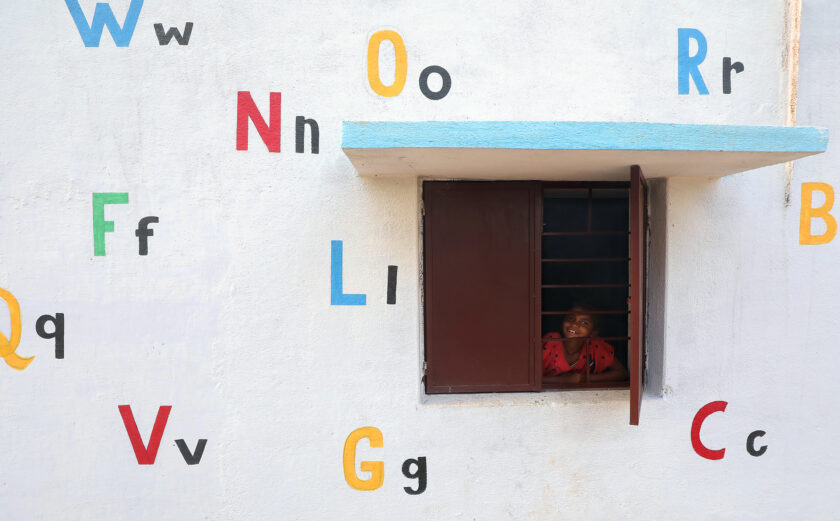

The data is clear—too many children worldwide are not learning. An estimated 244 million children and youth between the ages of six and 18 were out of school in 2021, and 771 million adults are illiterate.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated pre-existing weaknesses and problems within education systems across the globe. In 2020, the pandemic affected over 1.5 billion students, with 463 million unable to access remote learning when schools shut down. The inability to access remote learning most negatively affected disadvantaged households that lacked electricity, connectivity, and adequate devices and highlighted the already stark inequalities in education.

According to a 2022 report published by the World Bank, UNESCO, UNICEF, U.K. government Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, learning losses—characterized as “learning poverty”—increased by one-third in low- and middle-income countries.

The need for urgent action to prevent further educational disparities and regression has prompted three notable pieces of legislation to be introduced to the U.S. Congress:

- The Global Learning Loss Assessment Act (H.R. 1500 and S. 552): requires USAID to report on the impact COVID-19 had on the agency’s basic education programs.

- The Keeping Girls in School Act (H.R. 4134 and S. 2276): authorizes USAID to address social, cultural, health, and other barriers that adolescent girls face in accessing secondary education.

- The READ Act Reauthorization Act (H.R. 7240 and S. 3938): reauthorizes a law that requires promoting quality basic education in partner countries by expanding access to basic education for all children, and improving the quality of basic education and learning outcomes.

Education is one of the strongest instruments for reducing poverty, improving health, and ultimately, promoting peace and stability. Focusing on educational programs across the globe would mark an initial effort to institute a “new social contract” whereby the Global South does not bear the brunt of adverse events. Instead, we invest in the future through students and ultimately serve everyone’s interests. The current educational backslide has cost the current generation of students up to $21 trillion in lifetime earnings, which will most likely foster broader negative development impacts. Without this money present, poverty will remain prevalent and instability may ensue in numerous corners of the globe.

Neglecting education’s role in improving health would also prove detrimental. Pandemic policies and raging conflicts have negatively impacted the mental health of children around the world, prompting calls for increased funding for psychological health services. Educational access opens the door for vulnerable populations to receive nutritional meals, psychosocial support, and skills that enable them to make informed decisions. The result is a healthier young generation well-equipped to build and maintain robust economic, health, and social systems. Over time, this will help to prevent conflict and reduce the amount of humanitarian and development aid needed.

With policymakers around the world facing pressure to slash budgets as warnings of a global recession loom, cutting foreign assistance and international education funding may be tempting. Investing in students takes time to materialize, and they often cannot vote. However, if we are to build any semblance of a just, equitable, and prosperous society, significant funding must be allocated to drive transformative change. It is critical that we urge policymakers in the United States and around the world to support foreign assistance funding in the years to come, specifically for education.