U.S. Refugee Resettlement More Than #OneYearLater for Afghans and Beyond

One year ago, as the United States completed the withdrawal of its troops from Afghanistan, the Taliban quickly took control of the country. The group’s ascension to national power displaced nearly 1 million Afghans—nearly 182,600 Afghans crossed regional borders in search of refuge, and more than 777,000 became internally displaced, increasing their risk of becoming refugees in the future.

Today, tens of thousands of Afghans who fled the country are stuck in a legal limbo that prevents them from fully rebuilding their lives in new places.

After the Taliban seized Afghanistan’s capital city of Kabul, the Biden Administration evacuated around 76,000 Afghans to U.S. marine bases via the Kabul airport, where most were processed and then granted humanitarian parole—a temporary status designated by the Department of Homeland Security with limited rights.

While Afghans with humanitarian parole have access to some benefits—such as employment authorization—it is by definition a temporary status, and leaves a person’s path to permanent residency is uncertain. This week, however, the U.S. Congress introduced the Afghan Adjustment Act, a bipartisan initiative with historical precedent that could place Afghans with humanitarian parole on a path toward citizenship. This is a welcome and necessary step that would change lives. Yet, it has taken too much time to get here. The experience of many Afghans #oneyearlater—particularly those whose applications remain pending—shows how there is much work to do to build a U.S. resettlement program that applies equally to all.

Allies (and Sponsors) Welcome?

In August 2021, the United States rolled out Operation Allies Welcome, which provided pathways for specific groups of vulnerable Afghans to enter the country. The first channel, preexisting Special Immigrant Visas known as P-1 Visas, was limited primarily to interpreters and quickly became overwhelmed.

Under the second channel, the Priority 2 (P-2) designation, several U.S. agencies worked together to support a broader category of Afghans seeking refuge. Still, applicants required sponsorship from U.S.-based organizations and had to wait in neighboring countries to be approved.

On August 2, 2021, an InterAction statement noted that, “Application for P-2 visas requires individuals to flee Afghanistan and apply from neighboring countries. InterAction feels that this is unacceptable, as several critical border crossing checkpoints are now under Taliban control and Afghanistan’s neighbors may not necessarily welcome these individuals and their families.”

The U.S. government has not resourced or addressed the shortfalls of P-2 admissions, and the pathway remains extremely limited.

The State Department also facilitated a sponsorship program, Sponsor Circles, which allowed private citizens to help Afghans integrate into new communities. Although Sponsor Circles can alleviate caseloads from resettlement organizations, severe bottlenecks are blocking most applicants from becoming citizens. Location restrictions, burden of proof requirements—including for documentation that some Afghans had to leave behind for fear of identification by groups such as the Taliban—and a lack of U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) personnel to process applications are all preventing Afghans, and refugees from other countries, from finding durable solutions to their plight.

Recent legislative measures have been piecemeal and slow to gain traction. Before its eventual bipartisan introduction as a separate bill, language from the Afghan Adjustment Act was removed from a supplemental spending bill on Ukraine as Democrats charged Republicans with holding a double standard for vetting Afghans.

Another bill introduced in the House called for adding a mere 4,000 narrowly applicable Special Immigrant Visas without addressing capacity shortfalls in their processing. A Continuing Resolution on September 30, 2021, provided Afghan humanitarian parolees with the same benefits as services granted refugees—but only for up to one year.

Then, in March 2022, the Department of Homeland Security advanced Temporary Protected Status, first for Ukrainians and then for Afghans inside the United States for eighteen months.

These are not signs of a unified system—they are all disparate reactions to a systemic failure that provides limited temporary relief to specific populations.

Political Will Increasing?

The political will to address the refugee situation appears to be growing. The bipartisan Afghan Resettlement Act and the development of private sponsorship programs attest to that. Yet, advocates are impatient with the Biden Administration’s progress on restoring the infrastructure needed for a systemic approach that has sorely lacked.

The Administration has received bipartisan pressure to address the shortfalls of the Afghanistan evacuation and resettlement, and Democratic senators have recently called on the Biden Administration to increase its resettlement of refugees throughout 2022.

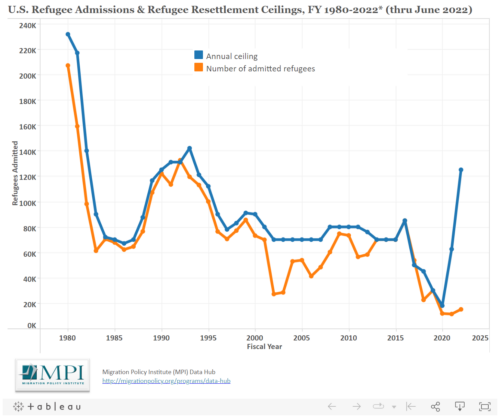

So far, the U.S. has admitted only 12 % of its annual target of 125,000 refugees. Only 500 of the 100,000 Ukrainians received by the United States since Russia’s invasion count toward this total. The rest have arrived through private sponsorship and temporary visas, duplicating the fragmented approach to Afghan resettlement.

A pilot program for a new Priority-4 designation set to launch in October would refer refugees already approved for resettlement under P-1 and P-2 categories to private sponsorship programs—which is helpful in alleviating some burden from the system but is not a substitute to a holistic refugee resettlement system that provides assistance and clarity around status and stay.

U.S. leadership has been missing even as the number of people forcibly displaced across the globe continues to rise year on year. The Biden Administration must take responsibility for the shortcomings of the refugee resettlement system and put human rights first—for Afghans and others—to reach its ambitious admissions target in 2023 and beyond.