Famine Risk & Prevention

Spot Report

Quick Summary

Global hunger and food insecurity are not new problems—both have steadily risen every year since 2014. However, as a result of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and economic downturns, the estimated increase in global hunger in 2020 alone was that of the past five years combined. As the global development and humanitarian sectors seek to lessen these crises’ impact on the world’s most vulnerable, one thing is clear: Without urgent intervention, global food insecurity will likely worsen, famine risk will increase, and more people will die. There is no time to waste.

Context of Global Food Insecurity & Malnutrition

In 2020, nearly one in three—2.37 billion—people did not have sufficient access to food. An almost exponential increase in food insecurity has forced over 34 million people into “emergency” levels of food insecurity as described by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) system. More than 41 million people around the world are now at risk of experiencing famine or famine-like conditions. Without transformational change, the world will not achieve the global goal of Zero Hunger by 2030, and the alarming increase in food insecurity and famine will likely worsen.

Widely accepted by the international community, IPC describes the severity of food emergencies. Based on common standards and language, this five-phase scale is intended to help governments and other humanitarian actors quickly understand a crisis (or potential crisis) and take action.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing food system challenges and vulnerabilities. Since the start of the crisis, the number of people experiencing famine-like conditions has increased to more than 520,000. In addition, the impact of COVID-19 on the global economy has caused extreme poverty to rise for the first time in 20 years. COVID-19 has worsened hunger and malnutrition, and the increased prevalence of hunger has contributed to the devastating impact of the global pandemic. The global community must focus on hunger mitigation and the intersecting issues of climate change, conflict, and economic instability to prevent worsening conditions of food insecurity.

While COVID-19 put tremendous strain on global food systems, it is important to recognize that global hunger increased steadily, with disproportionate impacts within communities, even before the start of the pandemic. For example, of the 690 million people who are food insecure in the world right now, 60% are women and girls.

Key Drivers of Food Insecurity and Malnutrition

Conflict: According to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report, more than half of the people who are undernourished live in countries experiencing violent conflict. Additionally, of the 155 million people around the world experiencing crisis levels of food insecurity or worse, nearly 100 million live in environments where conflict was the main driver of food crises. Political instability and protracted conflicts around the world disrupt harvests, markets, and trade while simultaneously limiting humanitarian access, driving increased food prices, and contributing to migration and displacement. Six of the ten most intense food crises were caused by conflict—in Yemen, Afghanistan, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Syria, and South Sudan.

Economic downturns: Economic downturns in 2020, caused primarily by the COVID-19 pandemic, affected almost all middle and low-income countries and contributed to worldwide levels of poverty. According to the World Bank, in 2020, 119 to 124 million people were pushed into extreme poverty. Governmental efforts to curb the spread of COVID-19 limited domestic economic activity and resulted in higher rates of unemployment and income loss. As a result of the extensive unemployment caused by the pandemic, there was a $3.7 trillion loss in labor income. This widespread economic slowdown impacted people’s ability to afford nutritious foods, especially given the rising cost of food globally.

Shocks and Stressors Caused by Climate Change: 98% of low- and middle-income countries were exposed to climate extremes between 2015 and 2020. Weather extremes were the primary cause of hunger in 15 countries and drove around 16 million people to crisis levels of food insecurity. Countries around the world, many already facing systemic fragility and weakened food systems, contend with increasing flooding, tropical cyclones, and drought. These climate-related shocks and stressors contribute to people’s vulnerability and impede famine prevention efforts.

COVID-19: The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated and compounded each of the above key drivers. More than a year since the start of the pandemic, the world is still grappling with urgent health needs and secondary impacts of the crisis. While the pandemic affected almost every aspect of global food systems, its impact on local economies was most destructive. In addition to its toll on the economy, physical restrictions instituted to curb the spread of the virus had problematic consequences for individuals and their ability to access affordable, nutritious foods.

Need for Early Action to Reduce Risks of Famine

All members of the international system must improve their ability to prevent the worst effects of hunger crises before they happen. Waiting for acute food insecurity situations to reach “Emergency” levels causes unnecessary harm to communities and is exponentially more costly and challenging to manage. Taking early action when there is an indication of growing food insecurity saves lives, reduces suffering, and is cost-effective. The global community has the expertise and the tools to predict where famine conditions are likely to occur and intervene early. It must utilize and act on this knowledge to better support frontline NGO actors to prevent famine and acute malnutrition in vulnerable countries before it happens.

Physical access constraints are a major barrier that must be overcome early to prevent famine. These constraints include generalized insecurity, attacks on humanitarian personnel and assets, government-imposed bureaucratic and administrative restrictions, donor-driven counter-terrorism measures limiting or otherwise blocking access to civilians in certain locations, and the behavior of non-state armed groups. Humanitarian organizations face significant bureaucratic and physical access constraints from all parties to conflict, hindering the timely and safe delivery of aid. Restrictions placed on the movement of civilians and supply chains negatively impact livelihoods and the ability of people to acquire food to feed their families, contributing to food insecurity and a rise in conflict. Additionally, strains on the humanitarian system from protracted conflicts and growing, competing demands and resourcing constraints limit the potential reach and effectiveness of food security programming.

Despite these real challenges, NGOs, local governments and communities, and donors have impactful solutions and programs to support communities facing famine or famine-like conditions. Still, often more political will and increased mobilization are needed to strengthen the impact and expand programs’ reach. The Country and Regional Context section located below provides several specific country contexts and programmatic responses from InterAction Member organizations.

Country & Regional Contexts

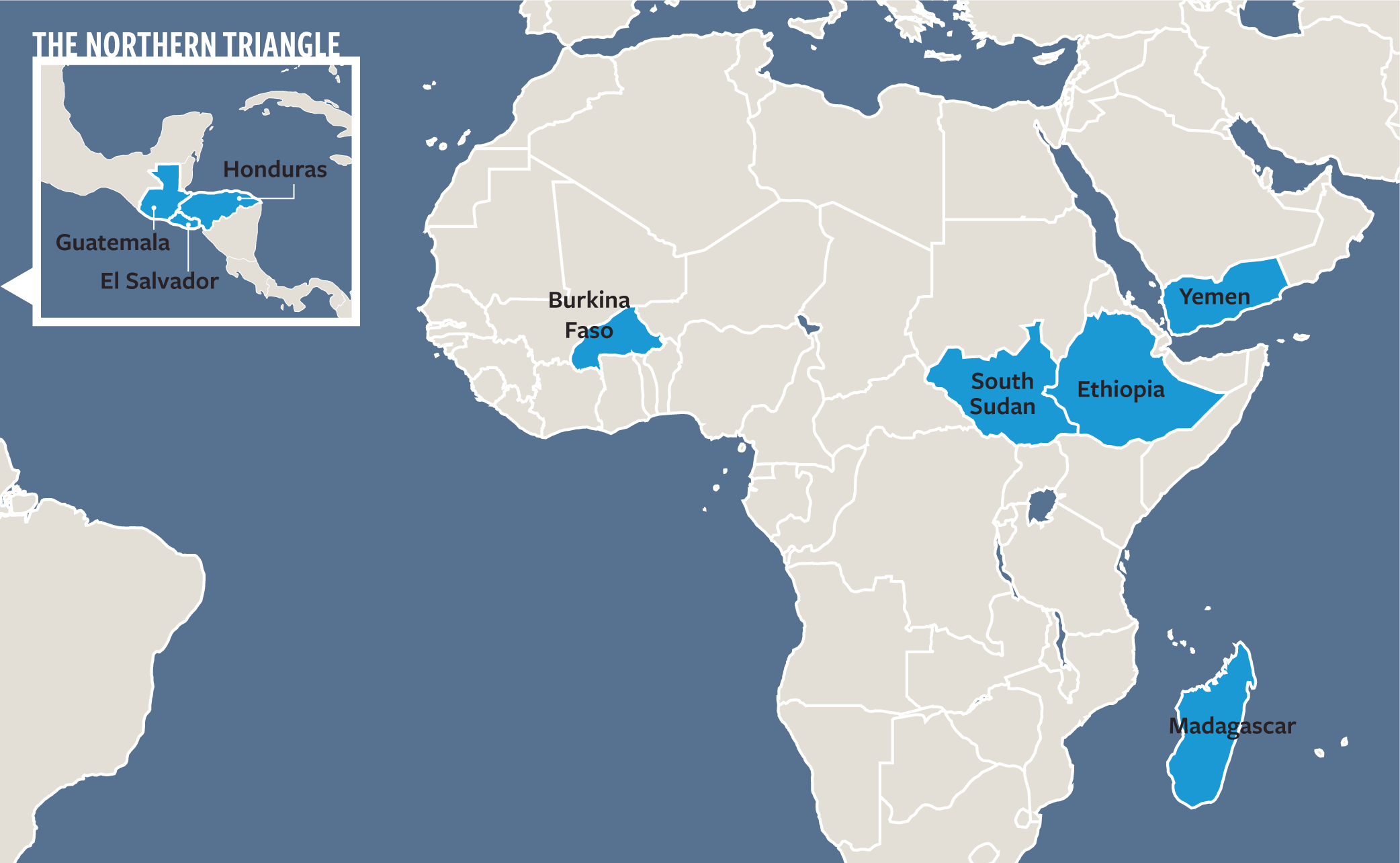

Drivers of food insecurity and malnutrition, and possible solutions and interventions, are unique to the country, community, or region facing the challenge. A handful of contexts below demonstrate a breadth of perspectives, levels of food insecurity, and challenges we face. These contexts are ever-changing, and descriptions are based on publicly available resources at the time of drafting. For example, at the time of writing, full information is not yet available on the impacts of current events in Afghanistan and Haiti on food security and nutrition. The country contexts and programmatic examples below highlight the diversity of food insecurity challenges and how famine risk and prevention actions are contingent on context. Stories from Southern Madagascar, South Sudan, Burkina Faso, and the Northern Triangle of Central America provide examples where current famine risk can be mitigated with increased early action responses. InterAction and Member NGOs are available to meet and provide more in-depth context and expertise for further understanding of country context.

Southern Madagascar

Nearly 1.14 million people living in the Grand South of Madagascar are experiencing acute food insecurity (IPC 3+), and around 14,000 people are in the Catastrophe phase (IPC 5). Children are particularly vulnerable; 500,000 children under the age of five are projected to suffer from acute malnutrition through April 2022. The key factors driving food insecurity in the region include three years of drought (the most severe drought since 1981), rising food prices, unemployment due to COVID-19, insecurity, and crop and livestock diseases. From January to May 2021, humanitarian organizations delivered assistance to more than 800,000 people living in the Grand South. However, given projections that indicate food insecurity will worsen between October and December 2021, increased support is needed.

CATHOLIC RELIEF SERVICES

Since 2018, CRS has collected real-time data (e.g., household hunger scores, food consumption, coping strategies, etc.) from project participants in southern Madagascar to track trends through the Monthly Interval Resilience Analysis (MIRA). These data are shared with the government, the U.N., and donors like USAID to contribute to food security reports such as FEWSNET reports and to advocate for response funding. MIRA found that household hunger scores from June 2020-2021 are higher

than the same period in 2018-2019, and food consumption scores are worse compared to 2018. MIRA provides strong evidence that the COVID-19 lockdown worsened food security in the Great South.Climate change compounded the impacts of COVID-19, as sandstorms buried fields. The conditions are dust bowl like and when talking to communities about their greatest needs, this always comes to the top of the list. In the spring, many people left villages for lack of food and livelihoods, but not everyone can or will leave. Households are doubling down on coping strategies, such as the sale of livestock and cooking implements, which has potential negative, lasting consequences. Since January 2021, CRS has provided 10,000 metric tons of food to over 220,000 people, but the needs continue to outpace the response.

South Sudan

Currently, 7.2 million people in South Sudan, 60% of the analyzed population, are experiencing crisis levels (IPC Phase 3+) of food insecurity. These stats reveal the worst state of food insecurity South Sudan has faced since 2011, with the northeast region experiencing the highest rates of famine. While increased humanitarian assistance has recently scaled up its response, the situation remains dire. Multiple intersecting shocks such as active conflict, flooding, displacement, poor crop production, limited access to basic services, and the cumulative effects of prolonged loss of livelihoods have contributed to food systems’ deterioration. Additionally, currency depreciation and its impacts on food prices have led to an economic downturn which negatively impacts people’s ability to access and purchase nutritious foods. Increased investment is absolutely necessary given that the $1.68 billion U.N. Humanitarian appeal has yet to be fully funded.

OXFAM

Oxfam is responding to the hunger crisis in South Sudan with lifesaving assistance, aiming to reach 102,00 people in the hunger hotspots of Akobo and Pibor with multisector assistance for water, sanitation, hygiene, food security, protection, and gender justice. The crisis in South Sudan is also a political one, which is why Oxfam also invests in good governance work with civil society and local and state authorities to empower communities to engage with traditional, local and national power-holders and promote accountability in the institutions and systems that affect their lives. Until governance issues are addressed, the humanitarian problems will continue.

Burkina Faso

More than 2.8 million people are projected to experience Crisis levels (IPC 3+) of food insecurity. The ongoing conflict, and the displacement caused by the conflict, are major causes of food insecurity and famine risk in Burkina Faso—where there were 1.7 million internally displaced people (IDP) as of May 2021. The violence and displacement has a significant impact on people’s livelihoods, ability to access nutritious foods, and capacity for agricultural production. Increased funding is imperative, given only 13% of necessary funds have been received as of May 2021.

Northern Triangle of Central America

In April of 2021, Vice President Harris announced that the U.S. would provide $310 million for assistance in the Northern Triangle. This funding is crucial given the rising food insecurity in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. According to the IPC, 3.5 million people in Guatemala are experiencing acute food insecurity (IPC 3+). Key drivers include the impacts of COVID-19, rising food prices, and worsening economic conditions. Communities in northern and southern Honduras and coffee-producing regions in El Salvador are also experiencing Crisis levels (IPC 3+) of food insecurity. From November 2020 to February 2021, 684,000 people in El Salvador were experiencing acute food insecurity, and there are currently nationwide Crisis levels of food insecurity in Honduras. The U.S. Administration’s investment in the Northern Triangle will provide $54 million for emergency food assistance and other relief needs in Guatemala, $55 million in Honduras, and $16 million in El Salvador.

LUTHERAN WORLD RELIEF (LWR)

With the sixth-highest level of chronic malnutrition globally, food security is an urgent issue in Guatemala. LWR, in collaboration with local partners FundaSistemas, is working to better nutritional outcomes for Guatemalan families while reducing chronic malnutrition and strengthening agricultural development. Applying innovative behavior change methodologies, the project uses home visits, technical assistance, and arts-based community development to promote healthy food consumption, agricultural diversification, improved maternal and child health, water, and sanitation. Through local partnerships, the project reduces stunting among children while increasing the availability of safe, nutritious food to rural communities. LWR began its work in Guatemala in the 1990s, with an increased presence since 2017. Promoting environmentally sustainable practices and championing co-creation, it supports farming families to improve health and nutrition, increase crop quality and yield, access sources of credit and sell produce in bigger and more profitable markets.

Ethiopia

Acute food insecurity in Ethiopia is likely to worsen, especially due to the conflict in Tigray, through January 2022. According to an IPC analysis, there are approximately 5.5 million people currently experiencing high levels of acute food insecurity in Ethiopia (IPC 3+) and 353,000 people are already in the Catastrophe phase (IPC 5). This is the largest number of people experiencing this phase of acute food insecurity since the 2011 famine in Somalia. IPC projections show that between July and September 2021, up to 400,000 people are expected to be in the Catastrophe phase. This widespread food insecurity is caused primarily by the conflict taking place in the country and the population displacement and loss of livelihoods that have occurred as a result.

WORLD VISION

World Vision, in collaboration with USAID, has been providing food aid to 624,009 food-insecure households in Ethiopia for Gegeo-Guji IDPs and returnees since 2018. World Vision was already working in West Guji and Gedeo before the displaced crisis started and was well positioned to respond. The response was focused on reducing the suffering of people in the conflict through multi-sector, multi-stage, and multi-agency interventions. In response to COVID-19, World Vision implemented a double rationing system to limit individual exposure. Food insecurity in this area has been aggravated by incidents of desert locust infestation, malaria outbreaks, and flooding. World Vision has provided 21,154 metric tons of food commodities for double distribution to internally displaced persons and returnees in 21 districts of Oromia, as well as the Southern Nations and Nationalities regions.

Yemen

In Yemen, conflict, economic shocks, and reduced humanitarian assistance are contributing to rising food insecurity. According to IPC projections, 15 million people are likely to experience Crisis levels of food insecurity (IPC Phase 3+) between April and October of 2021. It is expected that conflict will continue, further impacting production, inhibiting trade, and limiting humanitarian access to the country. According to an OCHA publication, around 80% of those in need live in areas “that humanitarian organizations consider Hard-to-Reach.” For example, in 2020, approximately 9 million people in need in Yemen were impacted by delayed or interrupted humanitarian assistance. Marginalized groups, particularly women and children, are most at risk of malnutrition and hunger. Over 2.3 million children under the age of five suffer from malnutrition in Yemen.

Policy Recommendations

To effectively combat growing food insecurity, the international community must embrace transformational policy, address the structural causes of hunger, and act nimbly and early when risks are identified. InterAction’s Food Security, Nutrition, and Agriculture Work Group encourages the U.S. Government to consider the following overarching recommendations. The InterAction Food Security Working Group is available for meetings to answer questions and provide context-specific recommendations provided below.

Prioritize early and anticipatory action as well as preventative and flexible programming to avert intensifying food insecurity and famine risk.

- Early and anticipatory action should take a ‘no-regrets’ approach, meaning interventions with positive economic, social, and environmental outcomes should be implemented even when it is unclear if a severely hazardous event like famine will take place. This type of programming aids the community even if the crisis turns out to be less serious of a threat as initially projected.

- Build crisis modifiers into current and future development programs to increase flexibility and mitigate hunger crises.

- Invest in the NGO community’s ability to conduct better, collective anticipatory analysis at the local and global levels, and increase funding to anticipatory financing mechanisms.

- Increase investment in climate-smart disaster risk reduction and disaster risk management interventions that protect and rebuild natural resources which simultaneously expand livelihood opportunities.

Increase flexible and multi-year funding to local organizations and continue to fund important food security accounts and initiatives.

- Strengthen multi-year, flexible support for community-based programming to assist local organizations in helping local actors drive more integrated responses and respond to community needs holistically.

- Mobilize additional humanitarian and development funding to complement G7 commitments around famine prevention.

- Increase support for strengthening or establishing national social protection systems. This includes providing more funding as multipurpose cash transfers or vouchers.

- Work in leadership with other global donors to fully fund the U.N. Global Food Security appeal.

- Continue to fully fund U.S. food security accounts, including Food for Peace, across the spectrum of emergency and non-emergency responses, including recovery and resilience-building interventions for vulnerable populations.

Encourage complementary programming to strengthen the connection between development and humanitarian action.

- Prioritize complementing short-term lifesaving support with longer-term solutions aimed at systems strengthening and addressing underlying drivers of crisis, including permitting International Disaster Assistance and Food for Peace Title II awards to better work together as appropriate to maximize efficiency and reach more people in need.

- Focus on the prevention and treatment of wasting in children in development and humanitarian settings with a focus on the first 1,000 days through multi-sectoral action.

- Ensure that women and girls, who are disproportionately affected by acute malnutrition, are at the center of prevention and response efforts to avert potential famines and support the most vulnerable.

- Support programming that assists low-income smallholder farmers, pastoralists, fisherfolk, and the urban poor to improve their livelihoods and increase investments in inclusive, sustainable, and resilient food systems.

Address the key drivers of food insecurity and famine risk.

- Promote consistent and sustained diplomatic action to prevent famine, protect citizens and ensure humanitarian access to areas of conflict. This action should follow international humanitarian and human rights law and be aligned with U.N. Security Council Resolution 2417, which prohibits the deliberate starvation of civilians as a weapon of war and protects agriculture and related infrastructure from attack.

- Engage diplomatically with countries to ensure that security operations do not undermine livelihoods and, if necessary, ensure safety nets are in place to mitigate the negative impact on civilians.

- Take into account the potential impact of sanctions and counter-terrorism measures on impartial humanitarian assistance and include specific safeguards, including humanitarian exemptions, to protect the delivery of lifesaving humanitarian assistance.

- Target and support the most vulnerable households and communities to adapt to and build their resilience to climate change and weather-related hazards, which are key drivers of food and nutrition crises and disproportionately affect children.

- Tailor programming to respond to the secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as disrupted supply chains, higher food prices, limited access to markets and agricultural inputs, and border closures restricting trade.

- Proactively engage on the legal and regulatory environment in countries at risk or experiencing systemic issues leading to famine to ensure the NGO community can register, operate, and move around to reach people in need, wherever they are located.

For more information or to arrange a more in-depth discussion on the issues identified in this spot report, contact Sara Nitz Nolan.

About InterAction’s Food Security, Nutrition, and Agriculture Working Group

The Food Security, Nutrition, and Agriculture Working Group is InterAction’s advocacy arm covering humanitarian and development issues related to hunger and malnutrition. Our working group supports legislative advocacy on all relevant food security, agriculture, and nutrition appropriations accounts; relevant bills and resolutions; engages with U.N. agencies and other multilateral organizations and entities; and ensures that Congress continues to prioritize food security and malnutrition as necessary components for implementing sound, impactful, and inclusive U.S. foreign policy.

About the Global Situation Report 2021

The Global Situation Report 2021 provides an overview of the most pressing humanitarian and development challenges facing the world in the next year. The report comprises an overview of global dynamics plus a series of timely, in-depth spot reports focused on country and region-specific issues that will be released throughout the year. The Global Situation Report 2021 is informed by the direct contributions of dozens of expert InterAction Members. Click HERE to view the full report.